The mainstream of economists and commentators has for years been hypercritical of Italian economy, which is considered fragile, immobile, innovative and competitive, and without a future. And, despite some obvious recent progress in Italy, the mainstream remains fundamentally pessimistic.

But what is the mainstream? By this term is meant a prevailing current of thought, especially among opinion makers. In the case of the Italian economy, the mainstream is negative across the board and even a bit self-congratulatory. What's more, as if the banal clichés that foreigners have sewn onto us over time were not enough, Italian mainstream has constantly carried water to the mill of such stereotypes, thus giving Italy the worst possible publicity abroad.

The mainstream's major criticisms of the Italian economy concern the high public debt/GDP ratio, the low R&D/GDP ratio, the small size of Italian enterprises, as well as productivity, competitiveness, and growth, all three of which are considered low. Moreover, a typical workhorse of the mainstream is the thesis of a progressive loss of purchasing power of Italian households, a sort of irreversible trend, that political classes and governments, especially the most recent ones, would fail to counter due to inability or lack of determination. Another fault of Italian governments, according to the mainstream vulgate, would be that of not being able to make “reforms” (except to be harshly criticized, as in the case of the Jobs Act, when they are made).

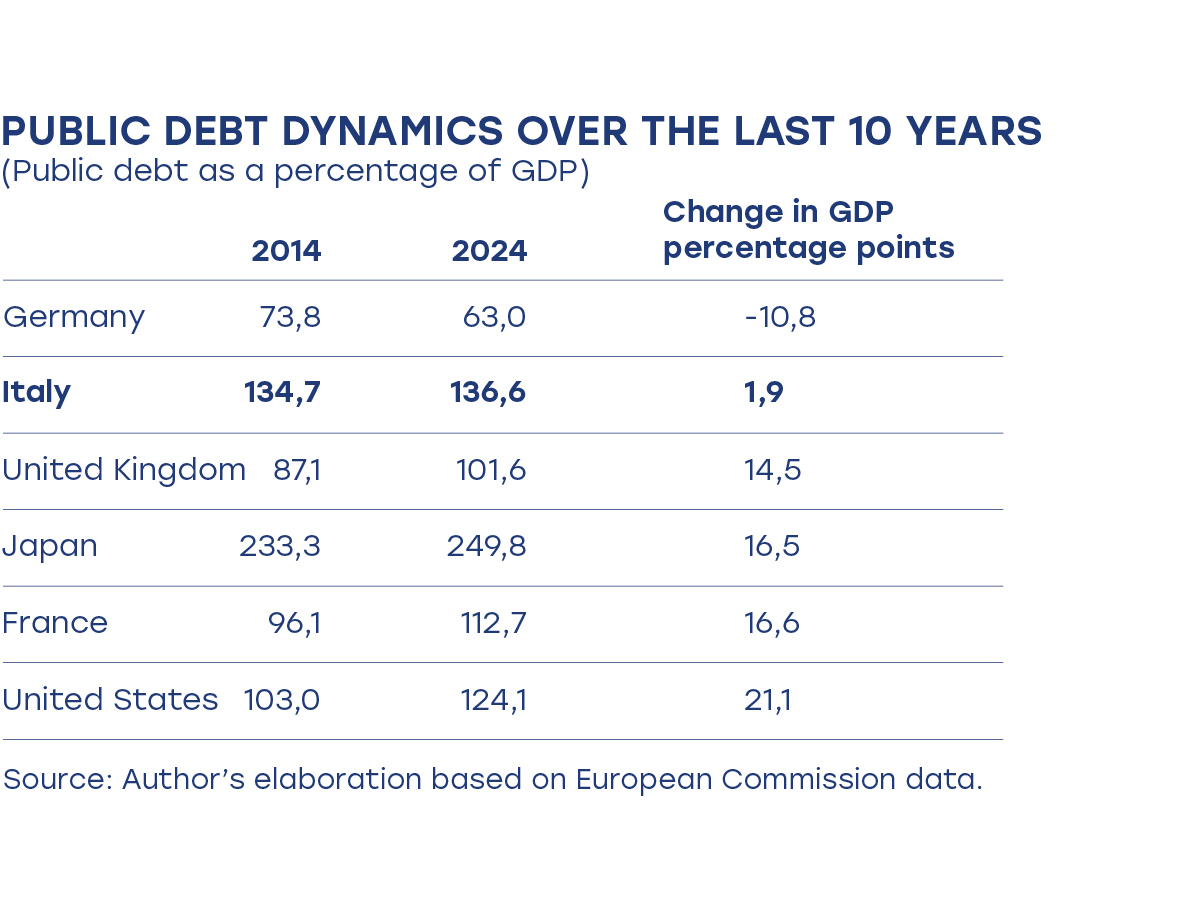

Ironically, many mainstream economists are of the “rigorist” persuasion, but they do not seem to be aware of the fact (or pretend not to be aware) that the greatest increases in debt/GDP and the sharpest falls in purchasing power of Italian households in the contemporary era have occurred during so-called “austerity,” that is, precisely when some of their favorite economic policy “recipes” have been applied to the letter. The ideal world of the mainstream, in fact, is one in which a Country with high debt/GDP like Italy has to forcibly produce repeated monstrous primary government surpluses, like 3% or more of GDP per year. This is ignoring the fact that such a policy would inevitably end up generating sharp falls in GDP itself, as in fact happened during the 2011-2014 “austerity” period, leading to an increase and not a reduction in the debt/GDP ratio, i.e., the exact opposite of what is desired.

The stereotype of “spendthrift” Italy

Assuming we believe that high public debt is a serious problem and that it is absolutely essential to keep it rigidly under control (we'd better not!), we absolutely disagree with the mainstream line. To continue to portray Italy as a “spendthrift” nation squandering public money at the drop of a hat, or even to go so far as to masochistically justify the low ratings given by rating agencies to Italian sovereign debt, as some mainstream “champions” have gone so far as to do, is to ignore:

- that now all major advanced Countries, except for Germany, have debt-to-GDP ratios above 100%; Italy is therefore no longer as it was 20-30 years ago, an almost isolated negative case, along with Japan

- that after austerity until the Covid Italy managed to reduce debt/GDP through a proper and balanced combination of growth and austerity, especially in the period of the Renzi-Gentiloni governments with the support of the economy minister Padoan, both governments moreover strongly criticized by the mainstream

- that after Covid and the exceptional injections of government spending that took place around the world, Italy is the only Country in the G-7 that has returned debt/GDP to pre-Covid levels

- that about half of Italian debt is firmly in Italian hands, thanks to Italy's high private wealth; another 20% or so is “parked” at the Central Bank (as a result of the support purchases of the past few years that have affected all European Countries to a similar extent, Germany and France in the lead); only a share of less than 30% of Italy's total public debt is financed by nonresident investors, i.e., one of the lowest shares in the EU; other high public debts, such as that of France, however, are financed by foreign investors for more than half of the total and are therefore more vulnerable than Italian debt

- that Italian economy is advanced, because from 1995 to 2029 has produced and will produce more government budgets in surplus before interest payments, i.e., primary surpluses; Italy, therefore, has a long history of being an “honorable” debtor Country and certainly not a “spendthrift” Country, since its debt has increased for repeated lustrum only because of interest payments

- that Italy's foreign asset position is largely positive (225 billion surplus at the end of the second quarter of 2024); this means that Italy's stock of private foreign claims (thanks mainly to repeated trade and tourism balance surpluses) is higher than Italy's public debt financed by nonresidents; other major EU Countries, such as France and Spain, have actually negative foreign asset positions, both characterized by liabilities close to 800 billion Euro

- that the so-called “S2” Index of sustainability of public debts in the long term in the face of future costs for pensions, health care and an aging population - an indicator developed by the European Commission itself - marks Italy as a “low” risk Country, while France, Spain and Germany itself are marked as “medium” risk Countries. This is thanks to those reforms that, according to Mainstream, Italy would not know how to do, including pension reforms.

Not only that. The mainstream seems not to have understood that today Italy's public debt in comparison with those of other Countries is among the most solid and under control. In fact, in these years, as in the past, most of the growth of Italian debt depends on interest while the growth of other Countries debt depends on increasingly large structural imbalances of states and local governments.

Consider, for example, the Italy-France comparison. In the past twelve months, from the third quarter of 2023 to the third quarter of 2024, Italy's debt increased by a total of 111.7 billion Euro, 85.4 of which (most of the increase), was due to interest. Excluding the latter, Italian debt increased in one year by 26.3 billion. In the same period, for comparison, France's public debt increased by 205.7 billion, of which only 56.9 was due to interest. So French debt excluding interest grew by a whopping 148.8 billion, or more than 5.5 times more than Italy's. The Himalayas of debt that newly appointed French Prime Minister François Bayrou has to climb, as “Le Figaro” wrote, higher and higher.

It is a fact that in Italy the general government primary balance, that is, the balance calculated before interest payments, has now been positive for two quarters: it was 1.2% of GDP in the second quarter of 2024 and 1.7% of GDP in the third quarter, after -5% in the first quarter. Thus, in the first nine months of 2024, Italy's primary budget has accumulated a relatively small overall deficit of -0.6% of GDP, which is now on its way to a possible balance at the end of this year and to a substantial surplus in 2025 and 2026, as predicted by the European Commission itself. This also explains why Italian spread, despite the “guffaws” of the mainstream, is trending downward and why foreign investors in recent times have overwhelmingly returned to confidently buying Italian government bonds (+96 billion since the beginning of 2024 through September), without, moreover, Italian debt becoming too unbalanced abroad, unlike that of France.

The improvement of public debt and the recovery of purchasing power of Italian households

According to seasonally adjusted statistics, over the past twelve months, i.e. from the third quarter of 2023 to the third quarter of 2024, the purchasing power of Italian households has tended to increase in real terms by 2.6%: in particular, it grew cyclically especially in the first quarter of 2024 (+1.2% over the fourth quarter of 2023) and in the following second quarter (+1.1% over the first quarter of 2024), while the progress of purchasing power slowed down somewhat in the third quarter of 2024 (+0.4% over the second quarter). These are remarkable figures, because after the surge in inflation they mark a strong recovery in households real gross disposable income, that is, income obtained using the deflator of final consumption expenditure (chained values with reference year 2020).

The mainstream and many commentators, as a rule, tend to almost always shift the responsibility for both the drift of public accounts and the deterioration of living conditions compared to 20-30 years ago onto the most recent years, without a minimum in-depth examination of the real causes and dynamics of these two variables.

The truth is that Italy's public debt today is certainly much higher as a percentage of GDP than in the years before the global financial crisis of 2009 but, in reality, it is virtually the same as a decade ago, despite everything that has happened in the meantime, from the Covid to the Russian/Ukrainian war. Similarly, while the per capita purchasing power of consumer households, calculated on raw data for the last four quarters, is still 6.8% lower in the third quarter of 2024 than it was in the second quarter of 2007 prior to the bursting of the global subprime mortgage bubble, it is also 8.3% higher than it was in the first quarter of 2014, which emblematically marks the end of so-called “austerity.” That is, government debt and citizens purchasing power are not inevitably doomed to worsen, and positive changes have already occurred.

The reality is that between 2008 and 2014, the Italian economy experienced a kind of “apocalypse” far worse, in macroeconomic terms, than the recent pandemic, with, in quick succession, the global crisis of 2008-2009, the financial crisis and the Greek debt contagion of 2010-2011, and the subsequent period of “austerity” from 2011 to early 2014. Since then, however, a long parallel “convalescence” of state and consumers has begun, although still not over. But, fortunately, for ten years now, albeit with some highs and lows, Italian public debt has been relatively back under control, while the conditions of Italian households, also thanks to a vigorous recovery in employment, are gradually improving.

In short: there was a before and an after, quite different. In fact, Italy's public debt, as a ratio of GDP, worsened from 103.5% in 2007 to 134.8% in 2014: an increase of as much as +31.3 GDP points, roughly equally distributed between the 2008-2011 period and the subsequent “austerity” period from 2011 to 2014. While in 2023, after peaking at 154.3% during Covid, Italian debt is back to 134.8%, that is, practically at the same level as in 2014.

World sub-prime mortgage crisis, Greece and “austerity” were, likewise, at the origin of a dramatic deterioration in the per capita purchasing power of Italian households from the second quarter of 2007 to the fourth quarter of 2011, estimated at -13.9% in real terms. This was followed, with the Renzi and Gentiloni governments, by a recovery in that purchasing power of 4.2% until the first quarter of 2018; a subsequent stationary phase with the Conte 1 and 2 governments until the fourth quarter of 2019, before Covid; then a substantial near return to pre-Covid levels in the first quarter of 2021, during the second phase of the Conte 2 government; a subsequent advance of 3.8% during the Draghi government through the third quarter of 2022; ending with the third quarter of this year, the date at which, despite inflation (which led to its temporary decline in 2022-2023), there is a further 0.8% growth in real household disposable income during the current Meloni government.

In the face of this data, should Italy endlessly regret what went wrong in the Italian economy between 2007 and 2014? Rather, let us look to subsequent progress and the coming years. Trying to keep the public accounts in order and further improve the living conditions of families. This is not impossible, because Italy is not in bad shape. As mentioned earlier, Italian debt/GDP is the only one in the G-7 that has returned to pre-Covid levels. While Italy's real per capita disposable income, adjusted for government transfers, is now about 27,334 Euro in purchasing power parity, practically like Denmark, which is at 27,948 Euro, and not far from the 28,758 Euro of a Country always taken as a model such as Sweden. In addition, Italian income is a good 2,730 Euro above the per capita disposable income of the ever-praised Spain, which is 24,613 Euro, and is much higher than those of Portugal and Greece (Eurostat data referring to 2023). Italy is therefore much closer than it might think to Scandinavia than to the Mediterranean, at least in this respect.

Low growth and innovation deficit: the wrong “key” theses of the mainstream

We will certainly not be the ones to ignore the fact that the Italian economy, like so many others, has its problems, the most important of which are an invasive and inefficient bureaucracy, high tax evasion, a still poorly liberalized services market, and a North-South divide that is, yes, narrowing but still has a long way to go.

However, the mainstream does not say one thing correctly when it states that Italian GDP has returned to low growth after the strong recovery of 2021-2022, citing as proof the double consecutive +0.7% in 2023 and that forecast for 2024, which are largely dependent on the slowdown of Italian industry due to the crisis in Germany and the automotive sector. In fact, the European Commission itself predicts that Italy's GDP will increase by a total of 2.3% in 2025-2026, which is more than the French, Japanese and German GDPs. This is no small achievement considering that the current higher growths of some other economies come more from the boost of population growth, while Italian demographics have been declining for years. So that, if we look instead at GDP per capita, the other major advanced Countries are all growing less than Italy, with Italy having a 2.9% progress in its GDP per capita over the next two years, compared with +2.8% in the United States, +1.7% in France, +1.5% in Germany and +1.3% in the United Kingdom.

Another pillar of the mainstream is to insist that over the past two decades Italy has been the advanced economy whose GDP has grown the least. Hence the stereotype of Italy as the “tail-end”. This is true, but it happened essentially because of the “lost” decade 2004-2013, characterized by the subprime mortgage crises, by Greece and by the very austerity that the mainstream itself still considers a “model.” The reality is that, in the absence of incontrovertible reasons, the choice of the length of historical periods over which to make time comparisons regarding the growth of different Countries is rather questionable. Indeed, on the basis of such a choice, anything and everything can be asserted.

To the mainstream it is easy to argue that, over the past ten years (2014-2023), in the G-7, Italy's GDP per capita was second in compound average annual growth rate only to that of the United States, and the “tailwaters” were Germany and France, not Italy. Similarly, if we take the last sixty years (1964-2023), i.e., consider a longer period unaffected by specific crises that occurred within a particular decade, Italy's GDP per capita has been exactly the same as that of the United Kingdom, one decimal higher than those of Germany and Canada, and only one decimal lower than those of the United States and France. In sum, except for Japan, which has grown the most since 1964 in the postwar boom, that is to say, the per capita GDPs of the other G7 Countries over the past sixty years have all increased at about the same rate.

Also cloying is the mainstream's constant complaining about Italian low R&D/GDP ratio, which they claim is one of the causes of Italy's alleged low growth. In reality, the R&D/GDP ratio is a misleading indicator because it is higher in Countries where the weight of research-intensive industries such as auto or electronics, in which Italy is less specialized, is greater. This does not mean that Italian industry is not innovative, as Eurostat has just recently certified that the share of firms active in innovation in Italy (63.1% in 2022) is the fourth highest in the EU-27, essentially equal to that of Germany (63.%), which is third in the ranking. It should also be emphasized that, contrary to what the mainstream says, Italy does R&D, and plenty of it, in its sectors of specialization: for example, Italy spent €1.8 billion on R&D in 2022 in non-electronic mechanics, where Italy is among the world leaders. Some problems remain, of course. In particular, in Italy the connection between the University and large institution R&D system, on the one hand, and the industrial system, on the other, should be accentuated. But the argument that the Italian economy is not very innovative is also completely unfounded.

Employment in Italy is at record highs

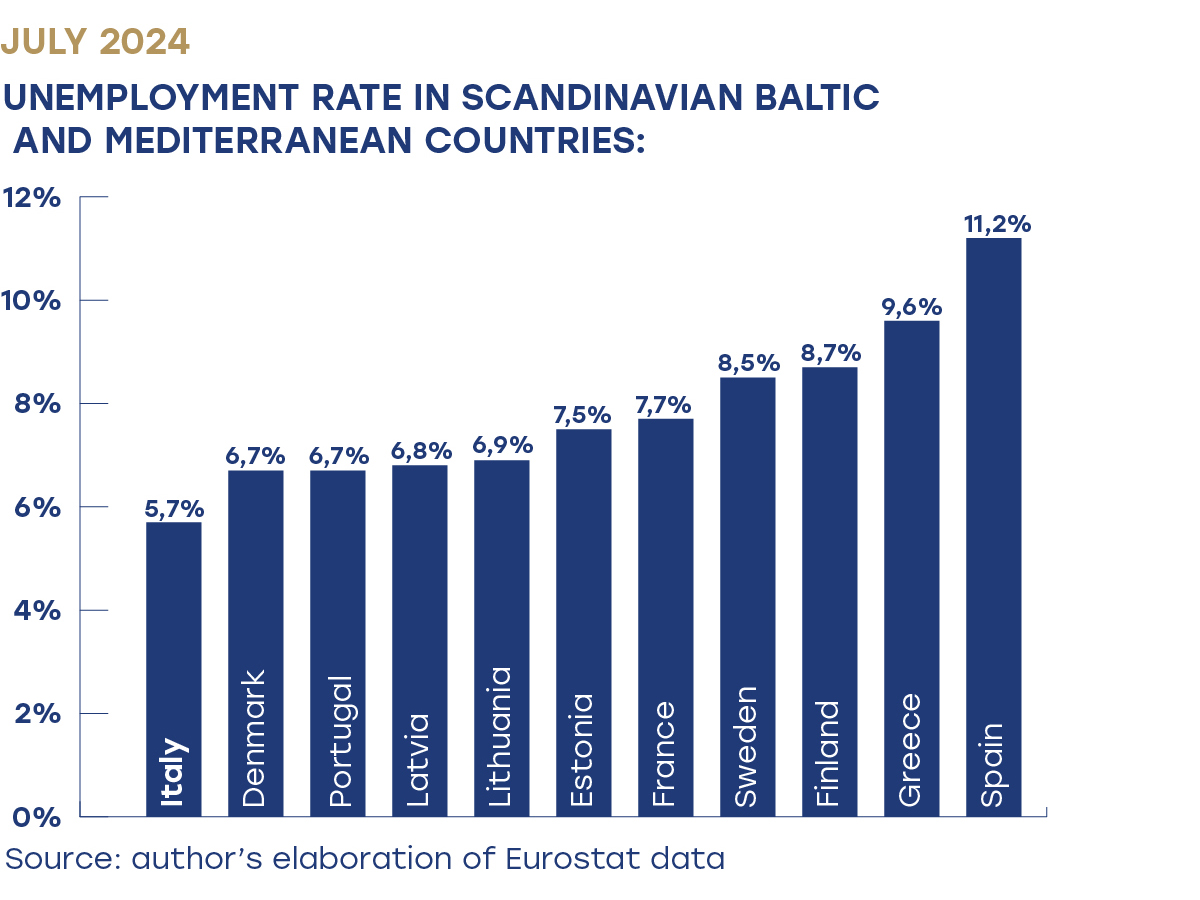

Another point that the mainstream seems to be ignoring or underestimating is the significant progress of employment in Italy. In fact, despite a slight decline in the number of employed term workers in November 2024, the labor market in Italy does not cease to reel in positive results. In November 2024, the unemployment rate fell to 5.7%, the lowest absolute value since the current ISTAT seasonally adjusted monthly time series exists, while the employment rate remained at 62.4%, an all-time high already touched in August and October.

In Europe, Italy's unemployment rate is now clearly the lowest among the Mediterranean Countries and, also, among the Scandinavian and Baltic Countries. It compares with Denmark's 6.7%, France's 7.5%, Sweden's 8.5% and Spain's 11.2%, a Country, the latter, where worrying levels of unemployment and poverty are hidden behind strong GDP growth figures. Italy's unemployment rate is also among the lowest worldwide and is close to the historically low values of advanced economies such as Germany (3.4%, also in November) or the United States (4.2%).

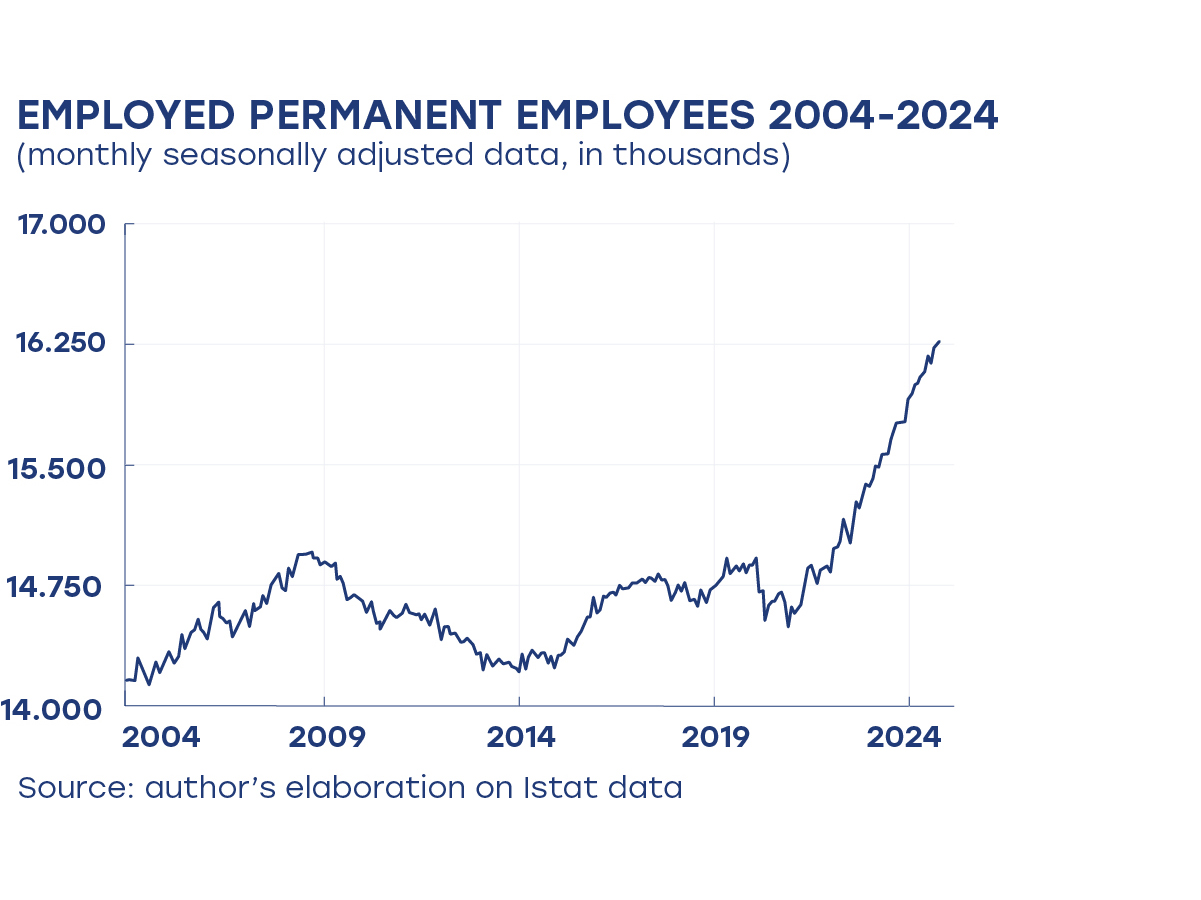

ISTAT data show strong growth in the number of permanent employees, that is, those employed on permanent contracts, belying unwarranted alarmism about an impoverishment of job quality and a widespread increase in precariousness. Criticisms that are not new. Strong misgivings were also expressed during the Renzi government about the effectiveness of the labor market reform, the so-called Jobs Act, and the social security contribution savings that accompanied it. And even then, the critics knife was mainly plunged into the hypothetical plague of precarious labor growth. Due to initial errors in ISTAT's estimates, which lingered for several months, corroborating these criticisms, the employed seemed not to increase as the reform's creators hoped. But then the initial estimates were sharply revised upward, and in the end, between February 2014 and May 2018, during the Renzi and Gentiloni governments, the total number of employed people in Italy grew by 1 million 257,000, of which 550,000 were permanent.

Once again, the increase in the number of employed, especially in the number of permanent employees, makes a vivid impression, with an unprecedented surge in permanent jobs well evidenced by the graph. In fact, after recovering to pre-Covid levels in October 2022, total employment in Italy grew by 820,000. In the same period, again from October 2022 to November 2024, permanent employees increased by as much as 991 thousand, i.e., by more than total employment, which in the meantime has seen the number of fixed-term salaried jobs fall by 337 thousand, and the number of self-employed increase by 166 thousand. Thus, we are in the presence of a significant increase in quality employment and a reduction in precarious employment.

Misconceptions about low productivity: another (false) workhorse of the mainstream

The data also belie the mainstream on productivity, which in Italy is certainly low in services but certainly not in manufacturing, where it is significantly high comparatively to other major European Countries. And this is despite Italian companies have to bear much higher energy costs than their competitors. Just imagine how much more competitive Italian industry could be if it could also have national nuclear capacity to support it, especially in the most energy-intensive sectors.

However, the above statement is not shared by those who dwell exclusively on aggregate manufacturing productivity data, thereby deriving an incorrect view of reality. This is because such data generate a kind of statistical astigmatism.

In fact, as documented several times before (most recently in Fortis, “If Italy beats Germany on the export and productivity front,” Il Sole 24 Ore, April 9, 2024, and “The extraordinary strength of the Italian manufacturing industry,” Il Sole 24 Ore, Nov. 14, 2024), considering only the average aggregate productivity of the manufacturing industry, the value added per employee in 2022 in Italy is 79. 660 Euro, which is significantly lower than Germany's figure of 96,170 Euro and France's figure of 85,810 Euro, higher only than Spain's figure of 68,660 Euro. If we were to stop only at this stage of comparison, as the mainstream does, Italians should really tear their hair out.

The explanation for the above aggregate figures lies in the huge number of microenterprises with less than 20 employees that characterize Italian manufacturing. These microenterprises, which number over 328,000 in Italy, obviously have low productivity and distort the average aggregate figure of Italian productivity. Does this mean that because of them, Italy's manufacturing industry suffers from a handicap against other Countries? Absolutely not. And we will demonstrate this by presenting a picture of manufacturing productivity comparing with the other major Eurozone Countries excluding microenterprises.

The importance of microenterprises in Italy: why criticize them?

Before doing so, however, we would like to point out a few things. First, Italian manufacturing microenterprises generated about 56 billion Euro in value added in 2022, a not insignificant figure that allows Italy to stay well ahead of France. Second, they are key in the flexible subcontracting networks of Italian districts short supply chains and have allowed us during and after Covid to perform better than all Italian competing global industries that have suffered from disruptions in global long chains. Third, with nearly 1.3 million employed, Italian family manufacturing microenterprises are a unique element of social stability in the world.

We might then ask whether microenterprises with their low productivity hurt Italian exports. No, because they participate only marginally in Italian exports, most of which are made by extremely competitive firms with 20 or more employees. So why should we give up on Italian microenterprises?

Of course, Italy should also create the conditions for having more and more medium-sized, medium-large and large companies: that is, to be even more competitive and to increase its chances of doing more innovation and internationalization. But this is another matter and does not mean that Italian industry is not already very innovative, very internationalized, and very competitive, that is, the exact opposite of what the mainstream says.

Italy is first in productivity in small, medium, and even large manufacturing enterprises

However, let us imagine, if only statistically, Italian manufacturing without microenterprises. What would happen?

First, according to 2022 Eurostat data, even giving up Italian microenterprises with less than 20 employees, Italy would remain the second largest manufacturer in Europe by value-added, basically with France.

Second, Italy ranks first in Europe in terms of value added per employee in both small, medium, medium-large and large enterprises. In particular, relative to Germany, the productivity of Italian medium-sized enterprises is significantly higher: 89,530 Euro per employee versus 72,740 Euro. And in 2022 Italy has resoundingly surpassed Germany even in enterprises with 250 or more employees: 118,970 Euro versus 116,250 Euro.

Third, if we consider all manufacturing enterprises with 20 or more employees, Italian average productivity, at 97,419 Euro per employee, is somewhat lower than Germany's 102,235 Euro. One might think that this is due to Italian smaller number of large enterprises, but this is not the case. In fact, Germany is ahead of us solely because of its specialization in the upper-middle segment of the automotive industry. So much so that, excluding the automotive industry, Italy is first in productivity in the rest of manufacturing as a whole: 97,487 Euro compared to 96,758 Euro for Germany.

In conclusion, only a careful reading of the data of enterprises with 20 or more employees can lead to an accurate understanding of the extraordinary strength of Italian manufacturing industry. Moreover, microenterprises, which are not included in the above numbers, are still to be considered an additional plus for Italy, not a minus, despite their low productivity.

Italian exports are increasingly competitive

Despite the slowdown in exports in 2024 due essentially to the implosion of intra-EU trade (caused by the German and French crises, Italian two main markets), the Italian production system is confirmed to be increasingly competitive, thanks to the investments in recent years in machinery and technologies favored by the Industry 4.0 Plan, the flexibility and dynamism of Italian companies, and the extraordinary differentiation of Italian exported products.

This is confirmed by the data of Italian exports in the first six months of 2024, a period in which, for the first time in contemporary history, total Italian exports exceeded those of Japan, placing Italy in fourth place in world exports (excluding the Netherlands, whose exports, for the most part, are represented by pure transit goods and re-exports). Probably in the second part of 2024, considering the low seasonality of Italian exports in August, Japan will overtake us again, returning to fourth. But Italian temporary fourth place among world exporters in the first six months of 2024 will still remain a historical fact, which no one could have imagined even a decade ago, when in 2013 the export of the Land of the Rising Sun was almost $200 billion higher than Italians.

The reality is that Italy is now an Economy capable of producing and exporting almost everything, with the exception of mid-to-high-end cars (like Mercedes, BMW, Audi) and energy. In fact, Italy is now very strong exporter not only of fashion, food and wine, furniture and tiles but also of mechanics, yachts, cruise ships and even pharmaceuticals (in packaged drug exports Italy has surpassed the United States and is now third behind only Germany and Switzerland).

It is enough to remove from trade statistics only the HS-87 item (i.e., vehicles), which, although very important for some Countries (such as, for example, Germany or Japan), accounts for only 8% of the value of world trade, to get a plastic idea of Italy's strength among exporters, its commodity diversification and its growing relevance in absolute terms gained in the field in recent years. In fact, in the remaining 92% of international trade, that is, in exports excluding vehicles, Italy now ranks fourth among world exporters (with $623 billion in 2023), behind only China, the United States, and Germany. Ten years ago (always excluding the Netherlands and also Belgium and Hong Kong for the same reasons), Italy was just ninth in world exports excluding vehicles, preceded by Japan, Russia, France, the United Kingdom, and South Korea. So, in just ten years Italy has made an extraordinary leap in exports, totally ignored by the mainstream, which continues to preach that Italy is an uncompetitive economy because it would have, in its opinion, enterprises that are too small, not very innovative and would also be characterized by a totally “wrong” and losing international specialization in the context of globalization. So much for the real data, which tells us instead the exact opposite.